Wow, the final inquiry post! It is truly hard to believe that I am already done. What an enriching process this has been. I have learned so much not only about inclusive education, but about the inquiry process. It was like I was inquiring about inquiry (how meta is that…)

One thing that I would say did not go so well was my inquiry planning document. Every week I would start out with great intentions: I would find some nice links, make a few notes… And then by the time Thursday rolled around, I would forget about it and my spreadsheet remained mostly empty. Now, this is not to say that I did not do my share of research. Rather, I would find information, make some bullet points on WordPress, and flesh it out from there. Is that necessarily a bad thing? Maybe not, but if I were to do this again, I think I could have gotten more out of it had I been a bit more rigorous with my planning document.

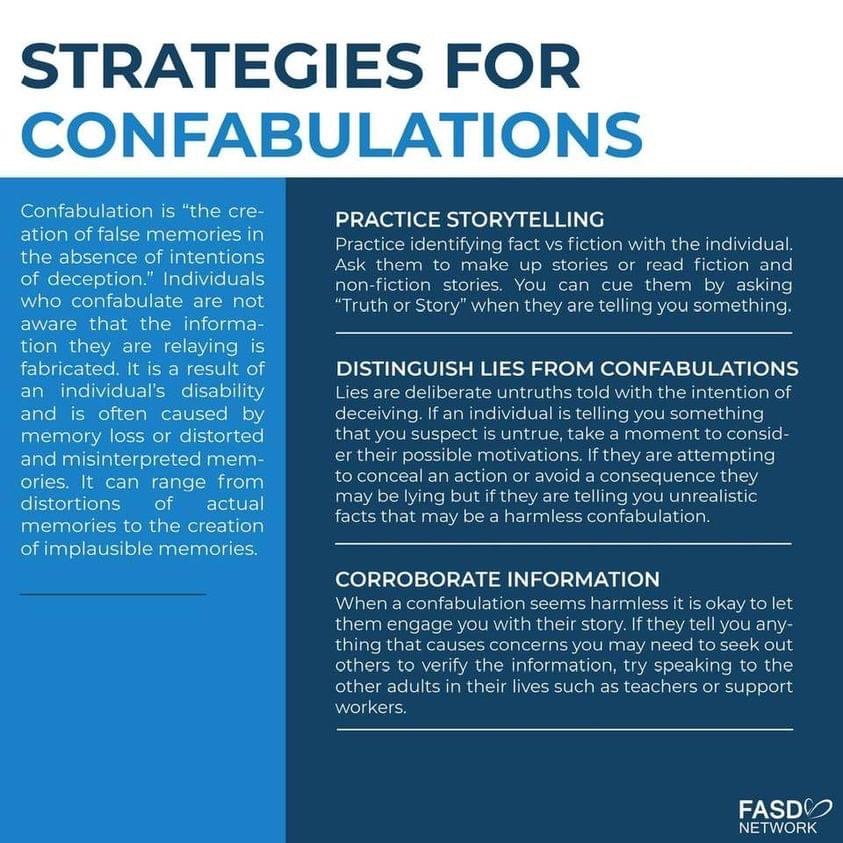

Another thing I noticed throughout the research itself was just how fluffy so many sources of information can be. Most sources I looked at from academics or professionals were full of vague language like “engage in culturally-competent, research-based practice grounded in an individual’s lived experience”, with no indication as to what this would actually look like. I understand that big-picture thinking like that is important… But I would be lying if I said I did not just want them to give actual tips as opposed to platitudes. That is why I tried to keep my blogs concise and practical. I wanted it to be useful, whereas many information sources I found seemed more keen on making the author seem important and intellectual (this is turning into another rant, so I will end it there!)

Now, what I loved about this process was the flexibility. I made a draft schedule for myself about which topics I wanted to cover, but sometimes, inspiration would hit and I would change it. And that was totally fine! I loved being able to deep dive into a particular topic each week without the pressure of it being graded or having to adhere to grading guidelines. I could just read and learn and share — and really, that is what inquiry is all about. Some weeks I went a bit more in depth, and others I scaled down, but I did not feel better or worse about it — they were just different processes.

Below, as one last goodbye to this inquiry blog, I have attached a screencast scrolling through my inquiry posts.

What a journey this has been! I would love it if all of my readers could share their favourite inquiry moments from their own blogs in the comments below. Please also let me know if you are interested in doing my PLN.

And with that, my EDCI 336 blog is complete. Thank you for all the support, and keep an eye on this space in the future!

YIT,

Markus